an excerpt from Letters from East of Nowhere: Daddy’s Words to Live, Drink & Die By (a memoir released in 2023. Grab your copy now)

Through letters and personal interviews, his eldest daughter conducts an inquiry into her father’s life, soon discovering that the book she intended to write is not the one that comes pouring out. Driven to tell her own story as she discovers letters from decades ago, the author relentlessly explores undiscovered incompletions from childhood while also carrying the narrative for her siblings, all of whom were at the effect of their father’s alcoholism.

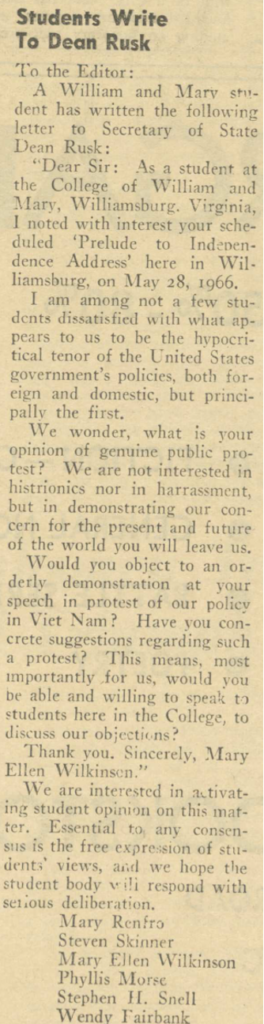

My parents met at a political action meeting—Students for Liberal Action, or SLA, as my mom recalls—about the Vietnam War. It was the fall of 1965, and my father was in his first year at William & Mary, the second oldest college in the country, in Williamsburg, Virginia, and my mother was soon to graduate.

(Which would have made her just 22 and he just barely 18. Christ! Still letting this sink in every time I think about it.)

Daddy had grown up in nearby Newport News, while my mother hailed from Maryland’s eastern shore. Back then, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel hadn’t been built yet, so her trips down to college involved taking long ferry rides from the southern tip of Virginia’s eastern shore to mainland Virginia, around Norfolk.

Struck by my father’s tall and lean form sitting there along the wall at the meeting, it was hard for my mom to not notice his dark, wavy hair and all around good-lookingness. My father carried himself with a confidence that drew people in. My brother TJ called it something like being a man of the people, someone who could converse with anyone, anywhere, about anything. My mother’s green eyes must have met my father’s at some point, and they hit it off and were soon seeing each other. Daddy had a tiny bit of a lisp, my mom says, though I can’t remember this about my father at all.

They found they had a lot of mutual friends who were also protesting the war and getting into the music scene. Daddy had a little Volkswagen bug at the time and apparently, according to his college friend Dick Losh, “he was the man with the resources” back then, giving everybody rides in that Volkswagen. My mother, on the other hand, found it challenging to make out in the backseat with a six-foot-tall man. For work on the side, Daddy was the night check-in guy at a motel.

While drinking was a huge part of their relationship from the very start, my mother conveys just how much the music and experience of being part of a movement was integral to their bond. Not to mention, they were bolstered by mutual friendships.

“Our friends were all partying like we did and felt the same way, politically. There was no isolation or feeling that we were different or outcast. We were part of the new world order,” she continues, quoting Jim Morrison. “It was like, ‘We want the world, and we want it NOW!’” (For any conspiracists, “new world order” in this context was often used to refer to “revolution” and counterculture in the 1960s.)

The summer of 1966, after my mother graduated from William & Mary, she and my father and their good friend Steve Skinner shared a cozy apartment on Richmond Road in Williamsburg.

“It had a little balcony,” she reminisces. “You could sit out there and take the air. It wasn’t that huge of a place, but we made out. Ed worked all night, but whenever he was off, we stayed up all night and played gin rummy and listened to the wonderful ‘60s music that was out—Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones. Everything on record players, of course.”

My mom will never forget the day my paternal grandparents came storming in. My Grandfather Clay’s words still echo in her ears all these years later.

“Y’all are livin’ like white niggahs!”

It’s still inconceivable to me just how blasphemous it was for a couple of unwed college kids to shack up in 1966 in Williamsburg. But my grandfather’s response was a stark reminder of just how big the gap was between generations—or at least between my grandparents and the hippie culture my mom and dad were becoming a part of. In fact, the term “generation gap” was coined in the ‘60s to describe that very phenomenon of distance between the beliefs and cultural norms ascribed to by young people vs. their parents. Incidentally, my mother’s parents were equally conservative, though not in the Southern way, and were none too pleased either with the freewheeling lifestyle on the horizon.

People of their generation and upbringing were still very much about appearances, reputation, and propriety. My parents, on the other hand, didn’t live under that guise at all. Living together was a total non-issue; they had no self-consciousness about it. The notion of living in sin—whether sin of the deeply religious kind or sin of the “don’t-make-us-look-bad” kind—meant nothing to them. Sin itself didn’t even register.

Contemplating that gaping divide, I always had it as mere coincidence that my grandparents on both sides were particularly conservative and against the union of my parents. It has taken a lot of thought and reflection for me to recognize just how radically different things were for parents of that era whose children were of the counterculture. The psychological limitations of my grandparents—that inability for them to grasp or relate to what was happening with hippies and the Civil Rights movement and anti-Vietnam War activism—accentuated by a desperate need to hold on to the last vestiges of 1950s wholesomeness must’ve been excruciating. In less than two decades, my grandparents would have heard the swoony melodies of their day turn into loud rock-n-roll and protest songs.

Suddenly, music took on all kinds of meaning that would expose any shallow, smarminess of previous generations, and all those nice-looking kids with crewcuts would soon become long-haired, bearded hippies who smoked weed.

Talk about beyond their command—an old world rapidly aging. I’m sure it was all a bit much.

When I try to relate to their parental freak-out, I reckon it’s something akin to when I’m having a batshitcrazymom day, like when my son locked himself in his room the night he was supposed to go for his Boy Scout rank interview and I had a deadline and it was the holidays and I’d had about enough of this bullshit and my husband’s, too, for that matter, so fuck this and I kicked the door in. Oh yeah, totally, I muse, in retrospect, I can pretty much see why any mom of any generation did any crazy-ass thing, like storming into the Williamsburg apartment to break up that hippie love fest and pot-smoking den of sin. Or in the case of my maternal grandmother, changing the wedding date in the date book so everyone would think the grandchild (me) had been born after marriage, not out of wedlock—as if anybody ever went back through the date book and gave half a shit.

In addition to their respective conservative upbringings, I have also pointed out to my mother that she and my father were both the first-born children of three siblings and came from families where they were never accepted for who they were. There must’ve been something about that, and the perfect storm that was the 1960s, but it’s nothing that she or my father recognized during their time together.

When my mother went off to Europe for a few weeks at the end of the summer of ‘66, she realized just how much she had fallen for my father. On her return in September, she landed a job as a teacher’s assistant at an elementary school, and she and my father got their own place together. By spring of 1967, there was some talk about getting married, although my mother says they weren’t sure how to go about it. In Virginia, you had to get a blood test, and there was some kind of waiting period she thinks had something to do with disease. So instead, they hopped in Daddy’s car and went off to North Carolina to get married, but when they got there, everything was closed.

“Besides we were both drunk and had driven all night, so that fell through,” she says.

Sitting across the table from my mother at a cafe in Wayne, Pennsylvania, I’m hearing this chronological telling of my parents’ early life together for the first time. I’m on my second latte, hanging on her every word. I had heard bits and pieces, highlights, my father’s version of something or my mother’s telling of the same. But now that I’m getting this collective history, I realize for the first time just how much I long to give voice to what they had as a couple before I came along, and before the other marriage and kids. It’s as though everything that happened between my parents was discounted because we were the divorced ones, my mother and me. My experience and understanding of their life together was suppressed for the sake of his other family, not because anybody made me do that, but it just seemed like that’s what had to be done. Only between themselves and with me could they exchange stories, laughs and memories.

To even put the words down, I have to summon courage from places I’ve never had to before to let my own experience and knowledge of my parents and their lives and my birth be freely expressed without hesitation or concern for how it might affect anybody else. Maybe it matters far less to others and is merely the residual concern of a child who learned to be careful about such things from an early age—fearful of offending, of creating jealousy or strife, of rocking the boat more than it was already being rocked.

After their botched elopement, my mother says she and my father started to drift apart. He had become good friends with Dick Losh, and a lot of drugs started entering the picture, according to my mom.

“I was feeling frozen out,” she says.

“I was able to find Dick Losh to interview for the book,” I’m bubbling, excited to share with my brother Jeffrey on the phone. “You know, Daddy’s friend in Colorado.”

“Who?”

“Dick Losh, you know, they rode motorcycles across the country to California together.”

“Never heard of him.”

“Wow.” I’m trying to process how it is that my youngest brother doesn’t know who Dick Losh is, given that my father was still traversing the country by thumb and stopping off in Colorado in his later years. “Well, they were the best of friends for like 50 years.”

Surely, Daddy would have mentioned him at some point. I’m guessing if the stories were to start coming out, “the guy he lived with in Maine in the same town you live in,” for example, there would be some recognition, but that earlier chapter was left untold or unasked about. I can’t tell which. And maybe it doesn’t matter anyway, except it’s the part I came from.

Which makes my conversation with Dick, a personal injury attorney in Denver, even more satisfying. Dick Losh. A name I grew up with. His name would come up when my mom and I were visiting mutual friends when I was a kid. Or in later years, my grandmother would mention he had called her house asking for my father. A connection. Someone who tied us all together, even though we weren’t anymore.

Dick launches into earliest memories of first meeting my father.

“Your father had the coolest record collection of anyone I’d ever met. Donovan’s Universal Soldier. Rolling Stones. Ed knew more about music and the counterculture of the day than anyone else I spoke with. He was up to date on everything from the lyrics to songs by Dylan and the Stones, the Beatles and so many others, all the way to the important issues of the time, as expressed by various groups of folks speaking out against the government.”

Dick lists civil rights activists down the line. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) with Stokeley Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, the Black Panthers, Eldridge Cleaver, Angela Davis, and the Chicago Seven, who were arrested during the 1968 Democratic National Convention for stoking anti-Vietnam war protest in Chicago. Renowned activists Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, along with David Dellinger, Rennie Davis, Tom Hayden, John Froines, and Lee Weiner were brought to trial for crossing state lines to incite riot and counter-cultural protests against the Vietnam War, among other things. (The Netflix original The Trial of the Chicago 7, out in 2020, tells the story.) Ultimately, all convictions were reversed on appeal.

Rennie Davis, one of the seven, died in February 2021. My parents were good friends with his brother Bob and wife Lynne.

“Your father definitely had his ear tuned to what was happening,” Dick continues. “Besides that, he was just a lot of fun to talk to and joke around with. He was generous to a fault, and a very good person.”

Here, Dick recalls, just as my mother had mentioned, my father had a lisp. “It may have been something that held him back a bit.”

At the time they were all in college together, the dean of the school was Carson Barnes, a relative of my father on my grandmother’s side.

“He didn’t care much for me,” Dick says, telling me the story about how he and his buddy were wrestling outside the girls’ dorm when the campus cops came along and busted them. “My buddy was graduating, going into the military, and I was in summer school. The dean told me not to come back on campus, but I told him I still had to come back to take a literature class and final exams.” Dick quit school after that.

The streets of Williamsburg were also a bit of a drag.

“We were kind of bad boys, always getting hassled by the cops. I got busted and went to jail for sitting on the curb with a black gal named Maria (who lived with Mary Renfro and her boyfriend Rick). Maria was also a committed virgin who didn’t want any romantic relationships. All I wanted to do was sit and talk to her, and the cops couldn’t stand it.”

Sometime after leaving school, Dick joined up with my father, who by then was working at Eastern State Hospital in Newport News, where my grandmother was a psychiatric nurse.

“We were psychiatric attendants, wore the white uniforms, had a wad of keys, the whole deal. People were in locked wards, and you had to restrain them and put them in seclusion, in straightjackets. It was shock treatments galore. This was before privacy as well. Some you’d meet on the street, you’d think they were normal.”

This is the first time I’m hearing details of the hospital stint and the basement apartment Dick and my father ended up sharing in Williamsburg. The guy upstairs’ father was one of the founders of Colonial Williamsburg.

“The landlord would try to lure us with a cheap six-pack of beer and some hot dogs and eggs,” Dick laughs. “The old boy was nuts, but we put up with him.”

Late at night, the two of them would come home cracking up about things that went on in the hospital.

“I’d be mopping floors, and some people would be walking around all night like zombies. There was one fella standing there in his mid-20s, doofy as they come, whether from meds they had him on or from an underlying disorder, and he would say, ‘11,000’—and he’d have this huge grin on his face. We were always wondering, 11,000 what? Money? 11,000 what?!”

Published in 1962, Ken Kesey’s book One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, made famous by the movie starring Jack Nicholson, provided a glimpse into the world of mental institutions of that era and the use of electroshock therapy—particularly for schizophrenia—although it was often used as a fear and control tactic on other patients because it would induce convulsions. Today, electroconvulsive therapy or ECT has been modified but is still effective in treating certain behavioral and mental health disorders.

In the ‘60s, talk therapy had barely emerged, and the only other option was for patients to be totally doped up. Dick conjures the memory of a guy who looked like Gollumm from Lord of the Rings.

“Talking to himself nonstop, up and down the halls, driving people crazy. ‘I’d do like Primo Carnera,’ he’d say, referring to this prize fighter, ‘right across the jaw!’ He wouldn’t shut up, so they doped him up on meds just like the movie. Another tiny guy was totally mentally deranged and breaking out of restraints and slashing his own throat. They shocked him a bunch of times. I saw one ECT that really worked, a guy who had slashed his own throat. It brought him back from being suicidal.”

I imagine my father having borne witness to all of this, more horrifically real perhaps than the story about pushing a guy out a third-floor window in San Francisco after having a box-cutter held to his throat.

When I contacted the San Francisco police and requested any reports with my father’s name or myriad addresses going back to 1998 (presumably this scuffle was in his uber-vagabond later years), I was unable to verify the tale. But slashed throats in a mental institution? My admiration swells.

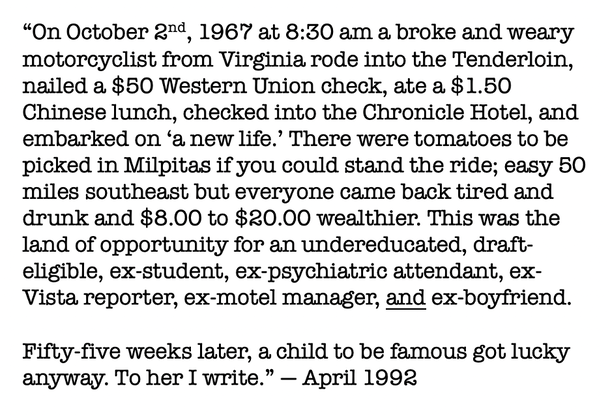

With the previous arrest charge from fraternizing with a black woman, plus the draft coming after him since he’d dropped out of school, Dick says, “We were feeling like outcasts, culturally disenchanted. Neither of us could stand the thought of going back to our hometowns, and the Williamsburg stuff seemed so picayune. We needed to strike out and have new experiences.”

They decided they needed to go out to San Francisco and check out the hippie scene.

More 60s counterculture excerpts in Letters from East of Nowhere.

Receive occasional news, info and author updates from author Kennerly Clay.